With the increasing introduction of multidisciplinary programmes in many of the universities across the globe, the academic core of English for Specific and Professional Purpose contexts has become complex and dynamic. One of the most significant influences of this and similar trends has been the recent efforts by many institutions to introduce and develop programmes which develop expertise in more that one discipline. This has also led to a gradual blurring of boundaries across disciplinary cultures in the world of academics. A necessary consequence of this development has been that in almost all professional contexts discourses are becoming increasingly interdisciplinary, complex, and dynamic (Bhatia, 1998).

The main purpose of this paper is to describe some aspects of the integrity of a genre (legislative provisions) from a well-established professional context (the discipline of law) to suggest how disciplinary considerations may create tensions within and across a range of academic discourse (Myers, 1992). (1) I would like to illustrate this integrity by giving examples of intertextual patterning within the discourse of law in order to show how it is used to serve the general function of textual coherence (Halliday & Hasan, 1976) and how it serves generic and disciplinary functions of making laws clear, precise, unambiguous and all-inclusive (Bhatia, 1993). This consideration of generic characteristics of specialist discourses is also meant to point out how we can enhance our effectiveness in specialist communication and help eliminate potential obstacles in the acquisition of professional and disciplinary discourse.

Of all the professional and disciplinary texts, legal genres display an overwhelming use of some of the most typical intertextual and interdiscursive devices, which often create specific problems in their construction, interpretation and use, especially when placed in interdisciplinary contexts. Legal specialists, with their extensive training and experience often find it relatively manageable to cope with such complexities. Professionals from other disciplinary cultures, however often find them rather unnerving. In this paper, I will describe some of these intertextual links in order to show you to what extent I think they are truly cohesive. By cohesive I mean that they provide the essential texture to legal texts (Halliday & Hasan, 1985). I will also describe to what extent I think they serve functions that go far beyond the normal textual considerations of their genre and become more legal in nature, and hence, accessible only to the privileged members of the specialist disciplinary culture.

Legal discourse, especially legislative provisions display a variety and depth of intertextual and interdiscursive links rarely noticed in any other discourse. Intertextual links in this professional genre seem to serve not simply the function of making textual and discoursal connections with preceding and preceded legislation, but they also seem to signal a variety of specific legal relationships between legislative provisions in the same document or in some other related document. As Caldwell, an experienced parliamentary counsel put it,

. . . very rarely is a new legislative provision entirely free-standing . . . it is part of a jigsaw puzzle . . . in passing a new provision you are merely bringing one more piece and so you have to acknowledge that what you are about to do may affect some other bit of the massive statute bookノ(Quoted in Bhatia, 1982, p. 172)

Let me give some more substance to the notion of intertextual links in legislative discourse.

Intertextuality

In a corpus of legislative discourse based on the British Housing Act 1980, I have found four major kinds of intertextual devices which seem to serve the following functions: (1) signaling textual authority; (2) providing terminological explanation; (3) facilitating textual mapping; and (4) defining legal scope.

Signaling textual authority

Textual authority(2) is signaled in the form of a typical use of complex prepositional phrases, which may appear to be almost formulaic to a large extent. A very typical example of this kind of signaling is the following provision from the British Housing Act 1980 (H.M.S.O., 1980):

110.5 The applicable local average rate is whichever of the two rates for the time being declared by the local authority in accordance with subsection (6a) below is applicable.

110.6 A local authority shall for such period not exceeding six months and . . . (a) the rate applicable . . . shall be a rate exceeding . . .

b) . . . the rate applicable to the sums left outstanding shall be a rate exceeding . . . .

In section 110.5, the use of the complex prepositional phrase in accordance with . . . , it signals a link to the text of the indicated subsections, it shows that we may expect some obligations for people affected by the British Housing Act in the indicated subsections, and it also indicates the nature of the legal relationship we can expect to find there. Our expectation is then met by the consistent use of the legally binding word shall in section 110.6. On the other hand, in section 13.4 below, the use of in pursuance of section 4(2) raises an expectation of rights depending on the individualユs choice. This is then confirmed in section 4.2 in the use of may, which is often used to express rights, rather than obligation.

13.4 The preceding provisions of this section do not confer any right on a person required in pursuance of section 4.2 to share the right to buy . . .

4.2 A secure tenant may . . . require that not more than three members of his family . . . should have the right to buy with him . . .

The use of under or by virtue of, on the other hand, is more neutral; however, many legal writers do not always use these expressions so explicitly, thus causing difficulties in interpretation. The manner in which textual authority is signalled (see note 2) is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Textual Authority

|

..... under ..... in accordance with ..... in pursuance of ..... by virtue of |

+

|

(the provisions of ) |

+

|

subsection....... chapter........ section...... paragraph...... |

+

|

of the ..... Act of the schedule of ..... instrument |

Providing Terminological Explanation

Terminological explanation is so central to legal writing that even the most common and ordinary expressions can take on special values in the context of law. House, flat, residence, injury, hand, defame, reputation, and many other words may require specialist interpretation because they may have different meanings in legal texts. So one of the main functions of legal writing is provide terminological explanation wherever such expressions are assumed to have deviated from ordinary meaning. The term charity, for example, has an ordinary meaning for most of us according to the society in which we live. But in the context of a particular legislative statement such meanings are often explicitly codified, rather than assumed to be known. Common understandings of such terms are often vague, flexible and less precise, but legal interpretation needs more precise definitions, as in the following section from the Housing Act (H.M.S.O, 1980):

2.1 The right to buy does not arise if the landlord is a housing trust which is a charity within the meaning of the Charities Act, 1960.

Facilitating Textual Mapping

The third major function of intertextuality in legal discourse is to signal textual coherence to the reader that text must be interpreted in the context of something expressed elsewhere. This is often signaled by the use of en-participle clauses, as in this section from the Housing Act 1980 (H.M.S.O, 1980):

54.3 The continuous period mentioned in subsection . . . (2) above is the period beginning with the grant of the protected shorthold tenancy and continuing until either . . . (a) no person is in possession of the dwelling- house as a protected or statutory tenant; or . . . .

If we compare the last two functions of intertextuality in legislative expressions (term explanation and textual mapping), we may find quite a bit of overlap, so much so that at some point they become almost indistinguishable. Typical realisations of these two functions include expressions from falling within the meaning of......, which clarifies texts, to referred to in subsection ......, at the other end, which is used for text-cohering. There are a number of others somewhere in the middle, such as specified in section ........., set out in subsection.......... or described in section .......and mentioned in subsection ....... The overlap can be summed up in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Terminological Explanation Textual Mapping

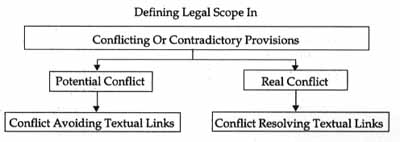

Defining Legal Scope

The final category of intertextual link often used in legislative statements I refer to as those defining legal scope for a provision. Since every single legislative statement within a particular legal system is seen as part of the massive statute book, and that none of them is likely to be of universal application, it is often more than necessary to define the scope of each of these legislative expressions. This is especially necessary when a provision may conflict with what has already been legislated. Legislative counsels often use intertextual devices in order to signal and to resolve such conflicts or tensions. In the case of section 16.1 of the Housing Act, 1980 (H.M.S.O., 1980) for instance, the writer simply signals the restricted scope of the provision in the context of paragraph 11(2) of schedule 2 of the Act.

16.1 The landlord shall be bound to make to the tenant - - -

(a) - - -

(b) . . . a grant of a lease of the dwelling-house for a term not less than 125 years (subject to paragraph 11 (2) of Schedule 2 to this Act); . . . .

In section 8.6 of the same Act, an anticipated conflict has not only been signaled but resolved too by providing that 8.6 will have legislative effect in spite of the conflicting requirements stated in the Land Registration Act of 1925 (H.M.S.O, 1980).

8.6 A charge taking effect by virtue of subsection (4) above shall have, notwithstanding subsection (5) of section 59 of the Land Registration Act 1925, be a land charge for the purposes of that section . . . .

Figure 2 indicates a more complete range intertextual device defining the scope of legal provisions:

Figure 2: Defining the scope of legal provisions

Conflict Avoiding Textual Links

Some of the most commonly used devices to signal conflicting cases are as follows:

- Listing of conditions which must be fulfilled for a provision to operate

- Listing of exceptions under which the provision ceases to operate

- Explaining/defining circumstances under which a provision operates

- Extending the scope of the provision

- Restricting the scope of the provision

- Specifying consequences of non-compliance of the provision

Most often these legal conflicts are signaled by the somewhat neutral complex prepositional phrase subject to, though often it is further specified by the modification of the noun phrase, such as the following:

. . . subject to the conditions stated in sub-section . . .below

or

. . . subject to the exception mentioned in section . . .

or

. . . subject to the limits imposed by the provision in section . . .

Conflict Resolving Textual Links

In the case of real conflict between provisions, one often finds two standard devices to signal a resolution of such conflicts. In the case of the new provision taking priority over the other one, the common device used is ...... notwithstanding the provisions of section........, which clearly signals that the new provision will operate in spite of the conflicting requirements of some older provision. In order to signal the opposite effect, that is, the new provision has no effect on the one previously legislated, one may often find the use of....... without prejudice to the generality of section..... Sometimes, we also find somewhat more general expressions to this effect, such as the following:

. . . in addition to the powers under section . . .

or

. . . instead of complying with the provisions of section . . .

However, such cases are rare. The parliamentary counsels more often than not go for established devices to signal conflicts, whether they are potential are more real.

Concluding Remarks

In this brief paper, I have made an attempt to describe only one of the genre specific intertextual devices to illustrate that, in addition to their text-cohering function, they also serve a number of typical legal functions, some of which give expressions to the demands imposed on the drafting community as a result of the generic expectations (Swales, 1990) on the part of the members of the relevant professional community. Textual coherence in applied linguistics is often viewed as independent of generic considerations and hence are often treated in literature as a matter of "linguistic" appropriateness (Halliday & Hasan, 1976) rather than "generic" effectiveness. With the increase in multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary exposure in academic contexts, it is becoming all the more necessary that such generic and disciplinary variations should be taken more seriously, especially in the context of English for Specific or Professional Purpose programmes. Ignoring such generic characteristics of specialist discourses means not only undervaluing effectiveness in specialist communication but also creating potential obstacles in the acquisition of professional and disciplinary discourse.

Notes

1. Bhatia (1993, p. 145) introduces the notion of generic integrity in the context simplification of texts. He claims that most professional genres are recognisable by members of relevant professional communities because they invariably display their typical characteristics, either in terms of lexico-grammatical features, rhetorical structures associated with a socially recognised communicative purposes. Most of us familiar with daily newspapers have little difficulty in recognising a news report and distinguishing it from an editorial, because both of them have their own distinct generic integrity. However, it is possible to create tension between two genres by incorporating typical features two different genres into one, as is being increasingly found in the mixing of promotional genres with a number of others, including academic genres (see Bhatia, 1998)

2. It is very rare to find legal provisions entirely freestanding. Whatever one may legislate at one any point in time is likely to have some effect on aspects of preceding legislation. Legal documents make use of typical set of lexico-grammatical devices to refer to the text(s) where relevant legal authority in stated. This complexity of referential relationships is typically mapped in most legislative provisions and is signaled by surface-level lexico-grammatical devices.

References

Bhatia, V. K. (1982). An investigation into the formal and functional characteristics of qualifications in legislative writing and its application to English for academic legal purposes. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Aston, Birmingham, U.K.

Bhatia, V. K. (1993). Analysing genre: Language use in professional settings. London: Longman.

Bhatia, V. K. (1998). Generic conflicts in academic discourse. In I. Fortanet, S. Posteguillo, J.C. Palmer, & J. F. Coll (Eds.), Genre studies in English for academic purposes (pp. 15-28). Castellon, Spain: Universitat Jaume I-Publicacions.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan , R. (1976). Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1985). Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social semiotic perspective. Melbourne: Deakin University Press.

H.M.S.O. (1980). Housing act 1980, Chapter 51. London: H.M.S.O.

Myers, G. (1992). Textbooks and the sociology of scientific knowledge. English for Specific Purposes, 11(1), 3-17.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.