QUICK GUIDE

Key Words: Pronunciation, Speaking

Learner English Level: all

Learner Maturity Level: Jr. High to Adult

Preparation Time: none, if this article's sample stories are used

Activity Time: 30 to 90 minutes

I. Phoneme discrimination activity for improvement of bottom-up listening and speaking skills.

Both speaking and listening require bottom-up processing: speaking requires clear articulation of phonemes, and listening requires accurate comprehension of phonemes (Celce-Murcia, 1991). Without phoneme discrimination skill, learners can neither express themselves nor understand others fully. Even though the specific role of phoneme discrimination in listening and speaking is not clear, phoneme discrimination skill certainly provides learners with increased confidence. Avery and Ehrlich (1992) argue the necessity of confidence in articulation as follows.

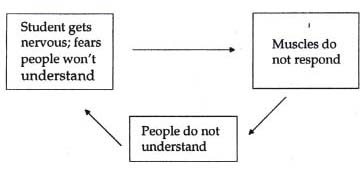

Figure 1: Nerves Cycle (Avery and Ehrlich, 1992, p. 222)

|

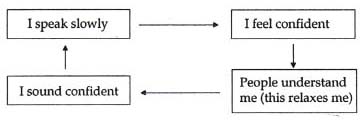

Figure 2: Positive Cycle (Avery and Ehrlich, 1992, p. 226)

|

As the figures above show, having confidence in articulation gives learners room to express themselves in conversation. This applies also for listening comprehension. Learners who are very familiar with phonemes should have confidence in discriminating sounds. Hence, I will explore a way to enhance learners' consciousness of phoneme discrimination.

II. Why not minimal pair practice ?

Minimal pair practice might seem effective for both articulation and bottom-up listening, and it seems popular for English conversation class as a way to familiarize learners with pronunciation. However, in reality there are several problems concerning this practice.

1. Minimal pair practice is often boring for learners because it is a one-way activity. It is like formal grammar instruction in the sense that a teacher gives instruction on how to pronounce sounds, shows examples, and corrects learners' pronunciation.

2. Learners may not learn phonemic differences, because minimal pair practice tends to be just meaningless pattern practice. Often non-native teachers do not know much about the characteristics of English phonemes. Those teachers tend to avoid asking learners to focus on subtle phonemic differences. On the other hand, some native teachers think that phonemes are too obvious for them to explain to learners. Too often, perhaps, native speakers of English tend to repeat the minimal pairs without explaining the differences. As a consequence of all this, learners have a hard time understanding the teacher's pronunciation and simply repeat automatically, without paying careful attention to the teacher's pronunciation.

3. In the EFL situation, learners do not know how to make use of this practice in an authentic context. There is little transfer from pattern practice to real language use. If minimal pairs are adopted in real sentences, learners tend to be confused and at a loss.

4. Some of the minimal pair words are not frequently used by EFL learners. Brown (1995) cites the example "ship and sheep", arguing that Singaporeans do not phonetically distinguish ship and sheep because there are no animal farms in Singapore. In any case, it is important to use familiar words in pronunciation practice; using unfamiliar words might make learners feel less motivated to learn, and they might lose interest in phonemes.

To resolve these problems and make English conversation class more effective, I would like to suggest an activity which stimulates students' imaginations and enhances learners' motivation. The activity is carefully arranged so that learners cannot guess answers from the context but only from what they hear.

In the next section, I will describe the storytelling activity and give two examples.

III. Procedure of the Story-Telling Activity

- The teacher provides a worksheet (see Appendix) to each student and reads the story.

- Students choose the words which they think the teacher pronounced.

- After all the students have finished answering, they compare their answers with other students.

- The teacher tells them the correct answers.

- The teacher arranges students in groups of three or four, and encourages them to reflect on how different each student's story is from other group members' or the model answers.

-

The teacher asks students to practice correct phonemes. For example,

- Student A reads his/her story, and student B guesses the answer.

- Student A reads his/her story to all the class, and the rest of the students guess the answer.

- The teacher asks students to make groups of five or six, and asks group leaders to read a story to student A, which student A conveys to B and so on. The last student's answer should be identical with student A's. The group which has the most answers correct wins.

IV. Conclusion

Learners' attitudes toward this story-telling activity were quite different from their attitudes toward minimal pair practice. They usually tended to repeat automatically for minimal pair practice. However, for the storytelling activity, they looked more puzzled if the story they had made did not seem to be correct, and they became eager to know the correct answers.

One of the biggest differences was that students paid careful attention to every minute of this activity while they did not do so for minimal pair practice. They even demanded more individual pronunciation checks and said that they wanted to be corrected on pronunciation in other classes, too. They were more motivated after this activity.

Minimal pair practice can often be boring and ineffective, but storytelling is interesting and lets students focus on phonemes in an engaging way. As a consequence, students will perhaps learn and remember better.

To increase the chances for learners to be involved in this activity, it is noted that the following conditions should be observed.

- Story-telling activities should include minimal pairs.

- Minimal pair words should be familiar to learners.

- Stories have to be coherent regardless of the answers so that learners can choose the answer without using top-down processing.

- Non-native teachers should be confident in discriminating phonemes or they should ask native speakers of English for help if necessary.

By creating a situation in which learners have to depend only on phonemes, their sense of awareness of phonemes will become sophisticated enough to be ready for confident interaction.

Appendix: Sample Stories

A. John went to buy some (1. shorts 2. shirts) the other day. But first he had to (1. walk 2. work) for several hours. After he bought them, he found a nice calendar with a picture of beautiful (1. glass 2. grass). On his way home, he met (1. Don 2. Dawn). They went to a coffee shop and talked about the (1. sheep 2. ship) which they had to paint for an assignment.

B. Alice asked her sister, Joan, "Would you (1. wash 2. watch ) my (1. cups 2. caps) for me?" "Sure," she answered. But later, she forgot to do it, and disappeared. When Alice came back, she found her brothers, who were playing with their (1. cards 2. cars). "Do you know where Joan is?" she asked. They smiled and said, "She said that she and Tony would go and see some (1. girls 2. gulls). Look, Tony gave us some very pretty (1. birds. 2. buds). Aren't they nice?"

References

Avery, P. & Ehrlich, S. (1992). Teaching American English Pronunciation. Oxford University Press.

Brown, A. (1995). Minimal Pairs: Minimal importance? ELT Journal 49:2. Oxford University Press.

Celce-Murcia, M. (1991). Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language. Heinle & Heinle.