Due to recent directives from the Japanese government, high school English teachers in Japan are under increasing pressure to conduct their classes mostly in English. This study explored the attitudes of Japanese high school students toward the use of English in language classes to better determine when and how teachers may integrate English and Japanese into their lessons. The researcher conducted quantitative and qualitative research, including action research, with 12 participants to devise pedagogy that high school teachers in Japan could adopt and implement to make better and more authentic use of English in the classroom. The results suggest that most of the student participants favour more classroom English use for the purposes of improving their speaking and listening skills. Pedagogy implemented following the research comprised specific tasks that teachers can adopt in their English classes to increase L2 use.

日本政府の近年の方針により、日本の高校英語教員は授業をほぼ英語で行わなければならないという、増大するプレッシャーの下に置かれている。本研究では、教師が授業で、いつ・どのようにして英語と日本語を使い分けるのが良いかをよりよく判断するために、英語使用に対する日本人高校生の態度を探究した。本研究者は、12人の被験者を使って、日本の高校教師が、授業で英語をより適切かつ本格的に使用する目的で、適用および実行可能な教授法を考案するため、アクション・リサーチを含む定量的および定性的研究実施した。研究結果は、参加した生徒たちの大半がスピーキングやリスニングスキル向上のために、教室内でより多くの英語の使用を好んだことを示している。研究結果を反映し、第二言語使用を増やすため、英語の授業において教員が採用できる特定のタスクを含む教授法がアクション・リサーチとして用いられた。

In 2011, the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)’s Commission on the Development of Foreign Language Proficiency stated in a policy document that in Japanese high schools “conducting classes in English is required to expand students’ contact with English, and to make classes a place for real communication” (p. 9). This has compelled researchers and English teachers in Japan to come up with new ways for Japanese English teachers to teach English, as it seems they can no longer rely on simply translating English texts into Japanese and conducting their classes mostly in Japanese (Miller, 2014). However, due to the concerns of many Japanese English language teachers and educators, MEXT announced in late 2019 that plans for a new, more communicative university entrance exam were to be postponed until at least 2024 (“Private English tests…”, 2019). In the interim, Japanese high school English teachers are expected to develop pedagogy that allows for lessons to be conducted in both Japanese and English to prepare their students for the coming changes to the university entrance exam and high school curriculum. This study investigates the attitudes of high school students towards speaking English and evaluates ways in which both English and Japanese can be used by students and teachers in the English as a foreign language classroom. Therefore, the main research question being asked in this study is: “How can both Japanese and English be used in the English as a foreign language classroom to assist in the acquisition of English?”

Using the L1 and the L2 in the Foreign Language Classroom

The argument for or against the use of the students’ first language (L1) in the second language (L2) classroom has been the source of much debate. Theorists against the use of the L1 in the L2 classroom would argue that students need maximum exposure to the L2 for acquisition and negotiation of meaning to take place (Ellis, 2005; Krashen, 1982; Littlewood, 2013). Researchers have pointed out that teaching methods such as the direct approach and communicative language teaching have allowed teachers whose first language is English to teach in many different contexts around the world due to an adherence to ‘English only’ rules in the language classroom (Miles, 2004). In Japan as well, not only MEXT, but many educational institutions prefer an English-only approach to English language education (Carson & Kashihara, 2012).

Proponents of the bilingual L2 classroom argue that students want their L1 to be used in the L2 classroom, and studies in the 1990s began to discredit English-only policies by showing how the L1 was more effective for teaching new vocabulary and difficult concepts (Atkinson, 1993; Auerbach, 1993; Schweers, 1999). More recently, studies have shown how contextual and motivational factors need to be taken into account when deciding on when and how often the L2 should be integrated with the L1 in the L2 classroom (Lee, 2013).

Concepts such as interlanguage (Selinker, 1972), interaction as modified input (Long, 1996), and L1 and L2 codeswitching (Turnbull & Dailey-O’Cain, 2009) provide legitimacy to the argument for not conducting lessons solely in students’ L1 or L2. Selinker (1972) argued that L1 utterances for most learners of a second language are not identical to that of their target language, and as such they generate an interlanguage to model the relationships between the different languages. By modified input, Long (1981) referred to interactions between speakers whereby they modify their speech during interactions to make themselves understood.

More recent research focuses on the pedagogical implications of L1 use in the L2 classroom with particular attention to when and how often to use it, along with the roles that students and teachers play in determining its use (Turnbull & Daily-O’Cain, 2009). Turnbull and Daily-O’Cain (2009) found that codeswitching was beneficial for both learners and teachers during a study of a German language course in Canada, and as a result argue for the “reconceptualization” of the foreign language classroom as a bilingual environment and language learners as “aspiring bilinguals” (p. 131). However, in the Japanese foreign language environment, and in particular the high school context, advocating for codeswitching and referring to Japanese high school students as aspiring bilinguals may prove problematic due to the often low levels of English learning motivation among young Japanese learners (Hayashi, 2009).

The fact that English is not used very often in English classes in Japanese high schools may be confusing to readers who are unfamiliar with the Japanese high school system. However, Japanese is widely used by Japanese English teachers in Japan as the main method of instruction, with heavy reliance on yakudoku (訳読 - the grammar translation method) to carry out their classes (Clark, 2009). Lee (2013) notes that this is in contrast to MEXT’s guidelines, which recommend an English-only policy in Japanese high school English language classes. He also notes that this reliance on the use of Japanese by high school English teachers in the English classroom has adversely impacted the students, specifically “regarding their attitude to the teaching and learning of English” (p. 1).

Methods: A Mixed Methods Action Research Study

This study was part of a larger project on English learning motivation involving a mixed methods action research study that combined quantitative analysis, qualitative thematic analysis, and action research. In total, 12 students (out of 320 who received an invitation letter) agreed to take part in the study, referred to here as participants A to L. They ranged in age from 15 to 18 at the time of the research and were all Japanese high school students in the school where the study took place. Two are male and 10 female. All 12 agreed to take part in an interview and complete a survey. Four agreed to keep a journal over the course of one academic year. Appendix B overviews the procedures and timeline of the research.

The survey was used to triangulate the interview data and to provide context for the interviews. While the survey included questions relating to the overall research project, only those related to the present study are discussed here. The survey used a Likert scale (see Appendix A) with 5 options: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Options 1 and 2 were interpreted as negative responses, while options 4 and 5 were interpreted as positive. Options 1 and 2 were explained as ‘not at all’ and ‘not so much’ respectively, while options 4 and 5 were explained as meaning ‘yes’ and ‘very much so’ respectively. The middle option, ‘a little,’ was interpreted as a negative response due to the Japanese translation of ‘a little’ being more closely related to a negative response. Also, the researcher provided translations for the parts of the surveys that Japanese colleagues believed participants may not be able to understand or may find ambiguous.

Interviews were carried out on an individual basis between the researcher and each participant using an interview guide that included a list of questions and statements from the survey. These were semi-structured interviews (Shoaib & Dörnyei, 2005), audio recorded in both English and Japanese, each lasting 15 to 30 minutes, which were then transcribed. The questions and responses from the interviews were grouped into themes relating to the questions in the interview guide. The themes were either pre-determined or emerged from the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006; King, 2004). For the action research part of the present study, the researcher and four of the participants kept journals to provide a more dynamic day-to-day record of what was happening in the classroom, how they felt about it, and a critical self-analysis of the students’ performance. Thematic analysis was used again to explore the data for recurring themes, with data gathered from the journals translated into English if originally written in Japanese.

Results and Discussion

Results relevant to classroom interaction in Japanese and English are discussed here. This includes a discussion of when and how often the participants think English and Japanese should be used by teachers and the students themselves, as well as the participants’ overall attitudes towards speaking English.

Students’ Overall Attitudes Towards Speaking English

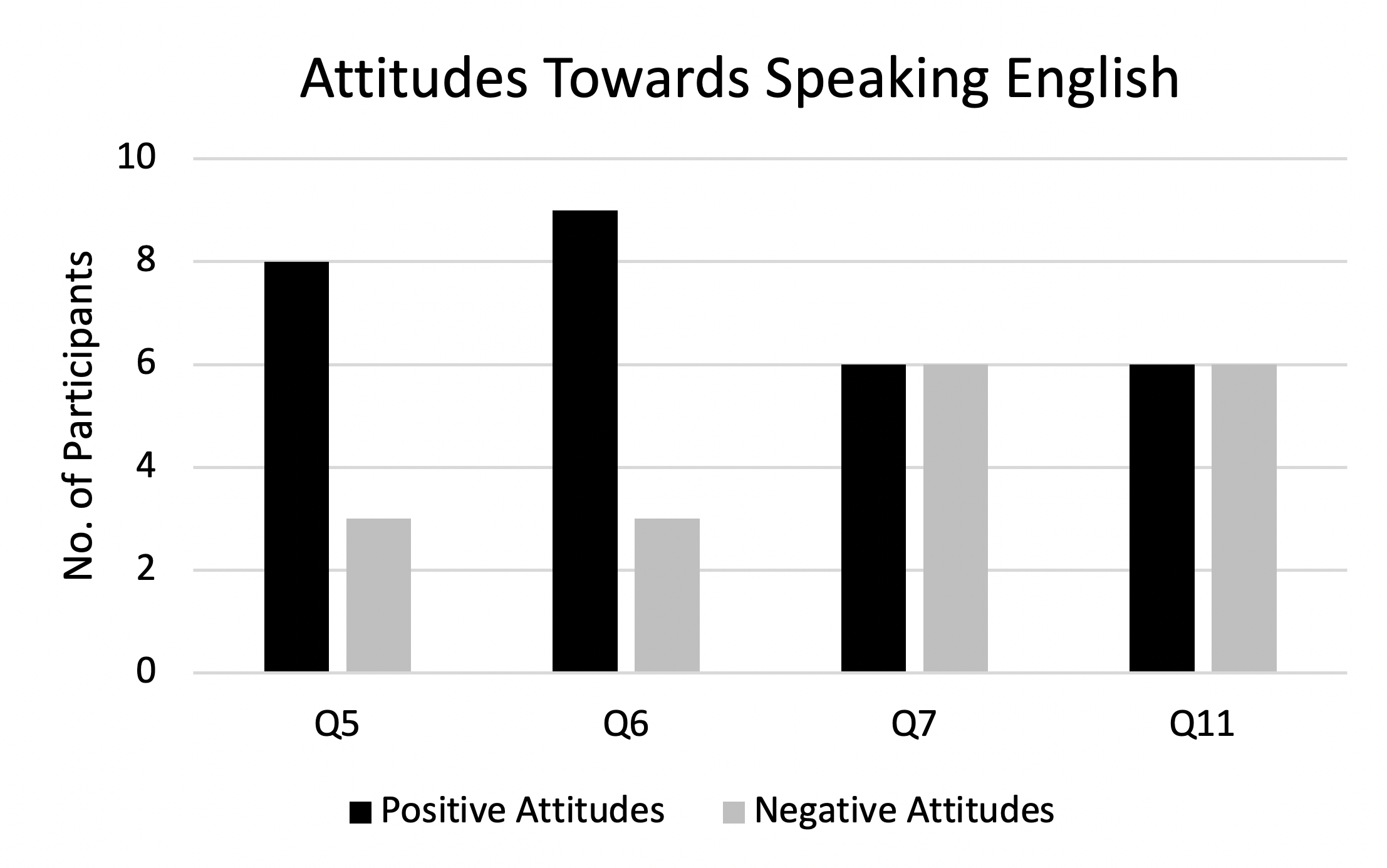

Questions from the survey (Appendix A) related to speaking English are the first theme discussed. Question 5 refers to speaking English with other students; 6 to speaking English with an English teacher; 7 to speaking English in front of the class; and 11 to speaking English outside of school. Figure 1 displays the results for these questions.

Figure 1. Attitudes towards speaking English.

In their answers to question 5, 8 of the 12 participants indicated positive attitudes towards speaking English with other students (1 did not answer the question). For question 7, 9 participants expressed positive attitudes towards speaking English with their English teacher. In responding to questions 7 and 11, half of the participants (6) expressed a negative attitude towards speaking English in front of the class and outside school. It is important to note that some of this unwillingness to speak English could be in part due to a general reluctance towards public speaking rather than being exclusively related to speaking in English.

Themes Concerning Students’ Attitudes Towards Speaking English

The thematic analysis from the interviews facilitated extracting more specific data relating to Japanese and English use in the classroom, from which three main themes emerged.

Theme 1: A desire to change the way English is taught at school in Japan

In their interviews, three of the twelve participants expressed dissatisfaction with how English is taught at schools in Japan. Participant H stated that she wanted to learn how to communicate in English and that she felt there was too much focus on grammar. She also stated that she would like to learn more practical vocabulary. Participant L stated that the most important thing was to learn how to speak English and communicate. Participant D argued for an ‘all English’ approach where students learn how to negotiate meaning with their teacher and think about what they want to say in class, rather than memorising texts. Most significantly perhaps, Participant A clearly stated that she believed Japanese teachers speak too much Japanese in class and should speak more English.

Berger (2011) used anonymous course evaluation data and surveys to investigate whether, as a teacher, her belief that using the L1 in her English lessons was what her students wanted. At the beginning of her study she was very much against her institution’s demand that the L1 not be used in the classroom. However, the findings of her research showed that it was indeed a good policy as even though the students liked having a bilingual teacher, they wanted teachers to use only English in the classroom. Researchers in Puerto Rico arrived at a similar conclusion on the use of L1 Spanish with students studying English, when they observed English classes led by teachers whose L1 is Spanish (Schweers, 1999). The results from the classroom observations were combined with the results of questionnaires completed by the teachers whose classes the researchers had observed. The findings showed that the majority of the students wanted teachers to use only English in the classroom. However, most participants also stated that Spanish should be used to explain difficult concepts, grammar, and vocabulary. This is a key point that seems to parallel research in Japan (Von Dietze & Von Dietze, 2007) and some of the present study’s findings.

Theme 2: An acknowledgement that Japanese is needed in the English language classroom

Participants C and K shared that if English teachers did not use Japanese in the L2 classroom, then it would be hard for them to learn. In fact, of the twelve participants, C and K were the only two who seemed hesitant about changing the way English is taught at school in Japan. It is important to note that they both carried out their interview in Japanese and as such their views could result from a lack of proficiency in English. Their views, however, would seem to add weight to the argument for the use of the L1 in the classroom.

Berger (2011) used the results of other studies and the students’ voices from her own study to conclude that: 1. Students do not mind the teacher using Japanese occasionally, 2. They like the teacher to use English, 3. They feel understanding the message is important, and 4. When and how to switch languages in the classroom should be considered. Even though Berger’s research was carried out in a university setting, her findings, in particular those related to considering when and how to switch languages, are also relevant to high school contexts.

In their study of whether Japanese university students prefer the L1 or L2 to be used in their university classes, Carson and Kashihara (2012) pointed out that for instructive use of the L1, beginner students often rely on L1 support in class more than advanced students. They also found that even though varying degrees of L1 use is necessary in the L2 class, depending on the level of the students, the participants in their study felt strongly that the L1 was not necessary for testing.

Cook (2001) also stated that when the L1 is used in the classroom, it should be used for negotiating meaning, explaining difficult grammar, and class management, even though he acknowledges that the level of learner L2 experience is also an important factor to consider. Cook stated that there are four basic merits to using the L1 in the L2 classroom. These are: 1. Efficiency; 2. It helps the learner; 3. It feels more natural and comfortable for the learner; and 4. It may have more external relevance in terms of how useful the L2 will be outside of the classroom. However, as stated at the beginning of this article, English classes in Japanese high schools are generally focused on explaining difficult grammar and the meaning of difficult concepts (Clark, 2009), and as such, this may leave little room for the use of English. There is therefore uncertainty surrounding when and how often teachers should use English in English high school classrooms in Japan.

Theme 3: A desire to try the ‘English only’ approach even if it is difficult

Participants B, E, F, G, I and J all expressed positive attitudes towards ‘English only’ even though they stated it would be difficult. In particular, participant I said that she “would like to try it,” and participant J stated that “English only would be difficult but I want to try it.” The English only approach is not widely used by Japanese teachers of English in high schools in Japan; in fact, the opposite seems to be the case (Clark, 2009). However, among ‘native speaker’ teachers of English, ‘English only’ would seem to be much more common (Ford, 2009). In his qualitative study, Ford (2009) interviewed 10 ‘native speaker’ university teachers of English in Japan and found that none of them had any system for using the L1 (Japanese) in their classes. In fact, 9 out of 10 of the teachers only used Japanese occasionally for humor or effect. Only one of the teachers stated that it was important to use Japanese for lower level students, in order to make them feel at ease and to show support to those students who “are dealing with required English classes” (p. 72). Ford concludes that when and how to use the L1 in the classroom tends to be “determined by pragmatism, individual beliefs, and personality” (p. 63).

English Learning Strategies Preferred by the Participants

The action research element of this study allowed for the examination of the day to day opinions of the student participants concerning their English classes. Specifically, in their journals they wrote about their preferred English learning strategies that they saw as a good way to improve their English speaking and listening skills.

That students would like to hear their teachers speak more English in the English classroom was a theme in three of the four journals. For example, Participant J wrote:

[English teachers] must speak English in the class. Because listening is very important to study English. —Extract 1, Participant J

Other references to a desire to listen to more English in the L2 classroom came from participants B and D. Participant B makes specific reference to a technique called shadow reading, which some English teachers use. She stated she enjoyed this activity and found that her listening ability improved since she was first exposed to it. By shadowing, she is referring to students reading along with the teacher at almost the same time, repeating what the teacher is saying almost simultaneously.

Enjoying active learning was mentioned by participant D.

I went to American school and I (found out) that active learning is so (much) fun. —Extract 2, Participant D

He calls for more discussion time in English in class and notes that, even though English-speaking opportunities are given in the L2 classroom, he feels students are given too much time to prepare and memorise what they want to say first. He states that on some occasions he has attempted to purposely not prepare or memorise before he speaks in English in front of a class to challenge himself. This, he adds, is despite him making mistakes and taking long pauses during his speech. However, Participant E would seem to disagree and wrote in his journal that he would like to have more time to prepare and write short essays.

During a previous study in a similar context (McCarthy, 2012), one of the participants, a Japanese junior high school teacher of English, stated that Japanese students prefer to think carefully and make preparations, preferably in pairs or groups, before they speak in front of a class. This, she believed, is due to a cultural and deep-rooted fear of making mistakes and therefore losing face. Participant D and E’s opinions seem to be diametrically opposed, with the former being more in tune with a more communicative style of learning which could be attributed to the fact that he spent time in an American school. On the other hand, Participant E is advocating for more time to prepare.

Brown (2001) stated that there are obvious advantages to an approach that removes the threat of “making blunders in front of classmates, and competing against peers” (p. 26), which could be associated with memorisation, where each student has the same objective. Therefore, taking these seemingly opposing views into account, the researcher developed pedagogy which allowed for the students to prepare before they produced the language, while concomitantly ensuring that they are integrating their own words and ideas with the target structures. In other words, removing the notions of memorisation and rote learning, while at the same time keeping the focus on form and authenticity, as the following suggested pedagogy shows.

The Researcher’s Journal and Suggested Pedagogy

The researcher also kept a journal over one academic year, making entries after lessons based on data from the surveys, interviews, and student journals. Several tasks were implemented and improved on upon reflection, which included integrating Japanese into activities for which the main language of instruction was previously English (see Appendix C for a detailed outline of a suggested task).

This suggested task integrates Japanese into the activity by allowing the students to speak Japanese when discussing the topic of the lesson. This enables free sharing of ideas and communicating in Japanese without English language constraints and inhibitions. The English is first integrated through translations in a word bank format, which is a list of key words and phrases in both English and Japanese that can be practiced with the teacher during a listen-and-repeat activity. This limits the teachers’ Japanese use and increases teacher talk time in English. As Japanese is used to scaffold the students during the word bank and pair discussion activity by assisting them in their understanding of the language and in idea generation, the final stage allows for maximum L2 (English) use. This final application stage also encourages the students to negotiate meaning in English with their partner and the teacher, rather than having them memorise and present their passages in a more controlled and less authentic way. Upon reflection and after changes were made to the implementation of the activity, the researcher/teacher included more vocabulary and grammar phrases in the word bank for subsequent lessons. Students were encouraged to refer to this during the application stage to help them answer their partners’ questions.

Limitations of the Study and Conclusion

This study has found a strong desire among the Japanese high school students examined here to listen to and speak more English in the English language classroom. It also reveals how and when Japanese high school English teachers can integrate English into activities that may be mostly taught in Japanese. This maximises English classroom use while concomitantly utilising Japanese to aid understanding during authentic and autonomous lesson tasks.

The limitations of this study are that it was based on a relatively small participant sample and conducted in one Japanese high school. As the participants volunteered to participate in the study, it can also be said that they potentially chose to because they like English, which might bias the findings. Future research into Japanese and English use in the Japanese high school classroom could be carried out on a larger scale while still utilising a combination of instruments with a focus on action research. As this was part of a larger project examining English language learning motivation, subsequent research could also emphasise the integration of Japanese in the English language classroom, which might result in more varied findings. Nonetheless, this study can benefit English teachers and educators in Japan and in other contexts who are interested in integrating L1 and L2 in their language classes.

References

Atkinson, D. (1993). Teaching monolingual classes. Longman.

Auerbach, E. (1993). Re-examining English only in the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586949

Berger, M. (2011). English-Only policy for all? Case of a university English class in Japan, Polyglossia, 20, 27–43.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy. Longman.

Carson, E. & Kashihara, H. (2012). Using the L1 in the L2 classroom. The students speak, The Language Teacher, 36(4), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTTLT36.4–5

Clark, G. (2009, February 5). What’s wrong with the way English is taught in Japan? Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2009/02/05/commentary/whats-wrong-w...

Commission on the Development of Foreign Language Proficiency. (2011). Five proposals and specific measures for developing proficiency in English for international communication. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology-Japan. https://www.mext.go.jp/component/english/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2012/07/0...

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), pp. 402–423. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.57.3.402

Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. System, 33(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2004.12.006

Ford, K. (2009). Principles and practices of L1/L2 use in the Japanese university EFL classroom. JALT Journal, 31(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTJJ31.1-3

Hayashi, H. (2009). Roles of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in learning English in japan: Insights from different clusters of Japanese high school students. JACET Journal, 48, 1–13.

King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), The essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 202–222). Sage.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. New York: Pergamon.

Lee, P. (2013). ‘English Only’ language instruction to Japanese university students in low-level speaking and listening classes: An action research project. Keiwa College Graduate School of Humanities. https://www.keiwa-c.ac.jp/thesis/2013/02/28/18495.html

Littlewood, W. (2013). Developing a context-sensitive pedagogy for communication-oriented language teaching. English Teaching, 68(3), 3–25.

Long, M. H. (1981). Input, interaction, and second language acquisition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 379, 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb42014.x

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413–468). San Diego: Academic Press.

McCarthy, A. (2012, March 20). What do the teachers say? Using Japanese junior high school English teachers’ opinions to develop a more context sensitive approach to teaching English in the classroom [Conference presentation]. English Board of Education Annual Meeting, Yamato City, Kanagawa, Japan.

Miles, R. (2004). Evaluating the use of L1 in the English language classroom [Master’s thesis, Centre for English Language Studies, University of Birmingham]. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/college-artslaw/cels/essays/matef...

Miller, K. (2014, October 7). What’s wrong with English education in Japan? Pull up a chair. Japan Today. https://japantoday.com/category/features/lifestyle/whats-wrong-with-engl...

Private English tests for Japan university entrance exams delayed after minister’s gaffe. (2019, November 1). Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2019/11/01/national/private-english-te...

Schweers, C. W., Jr. (1999). Using L1 in the L2 classroom. English Teaching Forum, 37(2), 6–9.

Selinker, L. (1972). Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 10 (3), 209–231.

Shoaib, A., & Dörnyei. Z. (2005). Affect in life-long learning: Exploring L2 motivation as a dynamic process. In P. Benson & D. Nunan (Eds.), Learners’ stories: Difference and Diversity in Language Learning (pp. 22–41). Cambridge University Press.

Turnbull, M. & Daily-O’Cain, J. (Eds.). (2009). First language use in second and foreign language learning. Multilingual Matters.

Von Dietze, A. & Von Dietze, H. (2007). Approaches to L1 use in the EFL classroom. The Language Teacher, 31(8), 7-10.

Andrew McCarthy holds an MA in Applied Linguistics from the University of Nottingham and a PhD in Applied Language Studies from the University of Limerick. His research interests include L2 motivation and learning, L1 and L2 interaction in the L2 classroom and CLIL. He is currently a fulltime teacher at Oberlin Academy High School in Tokyo. He can be contacted at andy@obirin.ac.jp.