In today’s fast-paced world, strong presentation skills are crucial across all disciplines, whether in class, at events, or in future career settings. The elementary English curriculum (MEXT, 2017) highlights speaking skills, separating them into two categories: speaking as an interaction and speaking as a product (i.e., presentations). In fact, most elementary school English units will include some form of presentation as an assessment. This is further reinforced in junior high and high school curriculums, stressing the need for presentation skills throughout education.

However, presentations are more than just memorising a script. To truly master them, students must develop clear articulation, appropriate volume, varied tempo, and effective body language—all while engaging their audience. In my experience as an assistant language teacher (ALT), I observed that many students felt anxious about public speaking and relied on rote memorisation as a result. Tackling this issue led to me developing a more interactive and engaging approach that focuses on continuous interaction in English at all stages of learning. Furthermore, I now use what I call “interactive presentations:” presentations that involve the audience and encourage real-time communication.

This article contains a step-by-step methodology that I applied in various English units during my time as an ALT. Although I focus on one unit as a case study, I believe these methods are adaptable to a variety of educational settings and grade levels. I hope to provide practical tools for educators to help students develop dynamic presentations that enhance both their language skills and overall communication abilities.

Context and Learning Goals

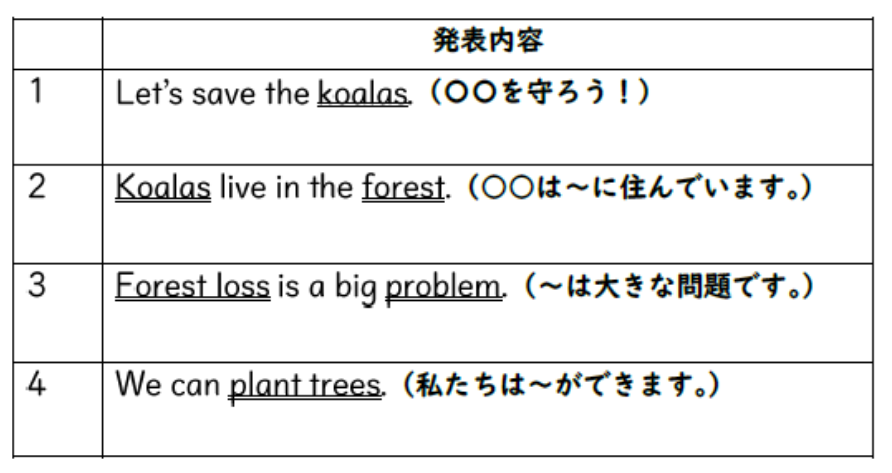

In this article, I will be looking at Unit 6 of the New Horizon Elementary 6 textbook (Tokyo Shoseki, 2004), where students discuss endangered animals using simple sentences (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Language Targets

In traditional elementary English classrooms, goals often focus on mastering specific content, language structures, or vocabulary. A typical goal for this unit might be: “Present about what we can do for endangered animals.” A lesson goal may look like: “Let’s learn the English words to talk about the problems animals face with our classmates.” Even though these goals give students a clear idea of what to expect, goals that focus solely on language (i.e., “present” and “learn the English”) can lead to an overemphasis on memorisation and language skills, rather than on actually using English to achieve a purpose. Without a deeper engagement with the content, activities and the final presentation can easily turn into memorising a script or dialogue.

Instead, I prefer an inquiry-based approach, such as: “Let’s research the problems animals face and discuss how to help.” This goal encourages both vocabulary development and critical thinking about real-world issues, rather than just language acquisition. Updating this goal also incentivises ongoing assessment focused on the learning process. Unlike traditional goals with vague expressions like, “let’s learn,” “discuss,” or “research” allow teachers to assess students’ participation in discussions, research tasks, and problem-solving activities. My approach sets the expectation that students will be assessed on their engagement with the content, with guiding questions to help students strategise their learning, like:

“Why are some animals in danger?”

“What can we do to help them?”

“How do we talk about environmental issues [in English]?”

Simple Japanese support, such as explaining phrases like, “Why are some animals in danger?” can aid understanding. Although we could simplify the goals in English, having them in Japanese first helps elementary students grasp the central idea before diving into English activities. Ultimately, we are assessing their engagement with the unit’s language, not their comprehension of the English used in the goals.

Modelling the Final Interactive Presentation

Traditionally, teachers model the final presentation at the start of the unit, usually demonstrating it live or showing textbook materials. These models tend to have simple and rigid sentence structures (see Figure 2). This strict rigidity often leads to students replicating the model and simply substituting key words to suit their chosen animal (see the underlined words in Figure 2), as students feel discouraged from experimenting with new language.

Figure 2

An Example Model Presentation

My approach is to instead begin the unit by modelling the “interactive presentation.” Students may expect to remain quiet and attentive during this model initially, as they would for any traditional classroom presentation. However, I break this pattern of passive listening by immediately asking direct questions, prompting students to move from silent listeners to active, engaged participants. In this unit, I began my presentation with the classic three-hint quiz, where students must guess the animal I’m thinking of. Then, I shared data about the declining koala population, encouraging students to think critically about the “what” (i.e., what is causing the koala population to fall?).

This approach brought out lively discussions in both English and Japanese. With encouragement from the homeroom teacher and myself, students shared their thoughts about the causes of koala endangerment in English. Some students enthusiastically shouted “Fire!” or asked, “Do you eat koala meat [in Australia]?” These moments allowed me to show photos of habitat destruction (i.e., “forest loss”) and elicit from students what we can do to help the koalas, such as planting trees or saving paper.

The language in my model presentation was initially complex for the students, but this was intentional. Teachers can use this method to model communicating difficult or unfamiliar vocabulary to an audience and show students how meaning can still be understood even without knowing every word—a concept I will explore further in this article.

Building a Shared Vocabulary

After interacting with the teachers during the model presentation, students become more engaged and eager to use the new language they’ve been exposed to. Even though textbooks often include vocabulary lists or dictionaries, I encourage students to generate their own language resources.

To do this, we revisit the unit goal and an inquiry question, such as, “Why are some animals in danger?” From there, we ask our students to brainstorm relevant vocabulary in both Japanese and English based on their existing linguistic resources. In my example, students provided “pollution” in Japanese and “no food” in English. This brainstorming session allowed us to create language tools, like word walls or flashcards, to further assist our students. I often hand-draw vocabulary generated in these sessions (see Figures 3, 4, and 5) and display them in the classroom. I also provide students with scanned digital copies, enabling them to review and access the vocabulary at any time. We then use these resources in activities alongside the included vocabulary in the textbook. By involving students in this process, we give them ownership over their learning and thus make it more likely that students will remember what they have learned.

The ultimate goal is not for students to merely memorise these new words, but for students to create a shared vocabulary that enables effective communication. Although students still learn the language targets alongside this generated vocabulary, this approach provides students with the tools necessary to engage in deeper, more authentic conversations in English.

Figure 3

“Plastic” Flash Card

Figure 4

“Disease” Flash Card

Figure 5

“Pollution” Flash Card

Supporting Planning and Collaborative Research (ICT Tool: LoiLoNote)

Early in the animal unit, students formed groups and chose an animal to focus on for their inquiry. We utilised the digital tool LoiLoNote for this stage, which allows students to collaborate in real-time, organise data, share ideas, and delegate tasks through its ‘shared notebook’ feature. For example, one student researched an animal’s habitat, while another looked for threats to that animal’s survival, then both students contributed their data through the shared notebook. This delegation of responsibility guaranteed that research was fairly divided among group members and that each student could take responsibility for their section.

Students collaborated in real-time, adding data to the notebook, brainstorming ideas, and used the information to talk with their peers in English-speaking tasks. This collaborative tool ensured active engagement for every group member and gave them ownership of their learning. While LoiLoNote was only used in the research phase for this unit, it could also be used for collaborative production by delegating sections of a poster (see Figure 6 for an example from another unit). The tool helps students build teamwork and communication skills, both of which are crucial to their success.

Figure 6

A Collaborative Poster About a Foreign Country

Creating Collaborative Presentations: (ICT Tool: Google Apps)

Once the research phase concluded, students transitioned to creating their presentations. They were tasked with developing a collaborative presentation using Google Slides. We set clear expectations from the beginning and informed students that a key part of their assessment would focus on how they interacted with the audience while presenting. This encouraged them to start developing strategies that went beyond simply presenting information, and to focus on how to engage the audience throughout their presentation.

Using Google Classroom, we created a space where students could access the presentation slides and any relevant resources. This was used in tandem with their research notes in LoiLoNote. With Google Slides, students were able to work on slides simultaneously and contribute ideas, images, and text to various sections to build their presentation (Figures 7 to 10).

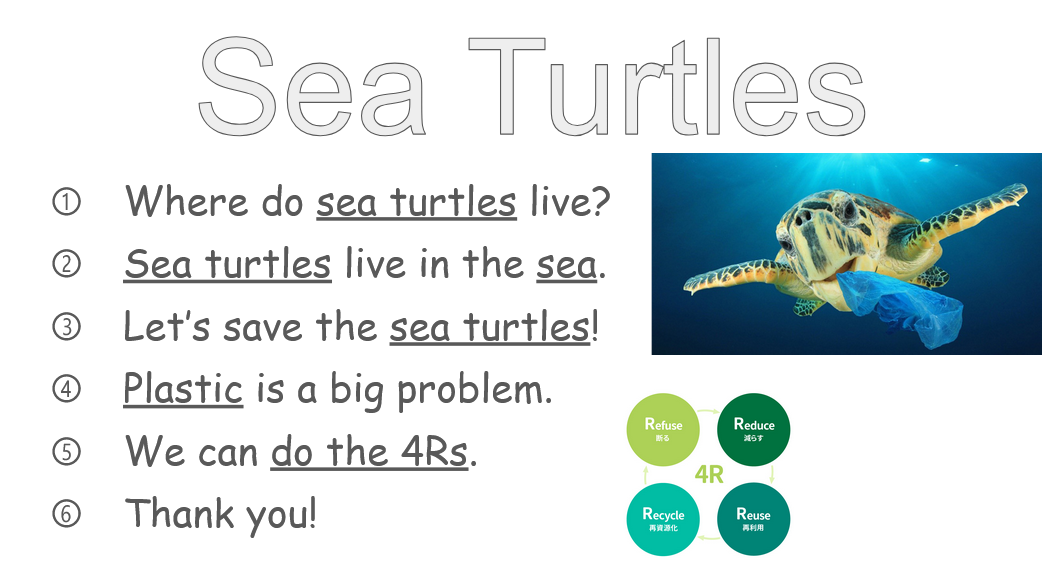

Figure 7

Presentation Start

Figure 8

Introducing Context

Figure 9

Establishing Problems

Figure 10

Discovering Solutions

Students created visually appealing presentations by embedding images, videos, and animations to support their points. They also discussed and planned where each member would speak, and shared strategies on how to engage the audience in English. In this way, students practiced communication skills with each other, even while creating the presentation.

Designing Presentation Strategies

As part of the creation process, students planned strategies to increase audience interaction and engagement during their presentation. Below are some key tools and strategies I recommend for any educator interested in using this interactive approach for their own classes.

Presentation Tools

- Displaying photos or illustrations

- Using visual aids to communicate difficult vocabulary not learned in class

- Including interesting animations

- Incorporating YouTube videos or audio

- Using props or realia

- Using gestures and body language and pointing at what area of a poster or slide they’re talking about

- Using target language from previous learning

Interactive Engagement Strategies

- Using three-hint quizzes to begin a presentation or break up long speaking segments

- Asking the audience simple questions, such as “Do you know/like…?” to encourage participation

- Randomly selecting audience members to answer an open-ended question, such as “What ...do you like?”

- “Opening the floor” for the audience to ask questions

- Performing mini-skits to relate learning to the audience’s lives

- Giving the audience prompting questions to guess the contents of the presentation (Figure 11)

- Quizzing the audience (Figure 12). Then, audience members need to guess or choose from a list of options

Figure 11

Questioning the Audience

Figure 12

Using Trivia Questions in Presentations

These strategies not only make the presentations more engaging, but also encourage real-time communication, requiring students to think critically and respond dynamically both as a presenter and as the audience.

Feedback and Rehearsal

In my classes, feedback comes in three forms: peer feedback, teacher feedback, and self-reflection. Peer feedback is used frequently during the rehearsal stage. Rehearsing is crucial for helping students build confidence and refine their presentation skills. It allows them to practice speaking, improve fluency, and develop their overall presentation style. Although we have groups practice together, we also have students practice individually using LoiLoNote, using a function that records their voice or takes a video. This tool allows them to review and improve their performance at their own pace either in class or at home. Students often share these recordings with the teacher or peers for constructive peer feedback.

This is where self-reflection is important in the rehearsal process. I encourage students to assess their own recordings, focusing on aspects like clarity, engagement, and the use of language. This self-assessment helps students become more aware of their strengths and areas for growth, which they can address before the final presentation.

Lastly, the homeroom teacher and I also provide general feedback to the class, focusing on body language, gestures, and audience engagement strategies. For example, we might suggest maintaining eye contact or using pauses or demonstrate techniques for handling mistakes during the presentation. We avoid singling out individual students for criticism but praise strong efforts when observed. This helps build a collaborative learning environment where students share ideas for improving their presentations.

Post-Presentation Assessment and Reflection

In this interactive presentation approach, assessment focuses on both the process and the product. Teachers observe students throughout each stage: research, collaboration, rehearsal, and delivery; formatively assessing how well students articulate ideas and engage with the content. Meanwhile, the homeroom teacher and I provide continuous feedback to help students improve.

For summative assessment, we use an “A/B/C” grading system, where we evaluate not only the content of their presentation, but also the use of body language, gestures, and audience engagement. An “A” student demonstrates minimal errors, uses a variety of language structures, and actively engages the audience through strategies, like asking questions or creating interactive moments. Most students will fall into the “A” or “B” range, with very few landing in the “C” level. Scores are kept private and shared individually.

Post-presentation reflection is also equally important. After their presentations, students write private comments on a self-reflection sheet on what went well and what could be improved. Peer feedback is given through tools like the stream in Google Classroom, where students can leave constructive comments in English and Japanese. We pre-teach useful phrases like “nice voice” or “it was interesting” to help students interact in English. These reflections, along with feedback, enables student self-awareness and helps them set goals for future presentations.

Finally, although I am cautious about relying on physical rewards, I do recognise their motivational value. Students often receive stickers for positive engagement, and students vote anonymously for awards like:

- Best Presentation

- Best Design

- Best Effort and Planning (teacher-decided)

Winners receive certificates, and the winners of the Best Presentation have their presentations recorded and broadcast throughout the school, offering them the opportunity to showcase their efforts and serve as role models for other grades. The winners of the Best Design have their posters or slides printed and displayed throughout the school.

Conclusion

By incorporating interactive strategies, collaborative learning, and ICT tools, our students gained confidence and developed strong presentation skills. They transformed from anxious speakers to real communicators, practicing language in context. The skills they have gained will help them not only in English, but in any future presentation. I hope educators will also be able to use these strategies to promote interaction in their classrooms.

References

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). (2017). Shogakkō: Gakushū shidō yoryō (Heisei 29 nen kokuji) [National curriculum standards for elementary school (2017 bulletin)]. https://www.mext.go.jp/content/1413522_001.pdf

Tokyo Shoseki (2004). New horizon: Elementary English course 6. Tokyo Shoseki.

Kye Marksteiner is an experienced elementary school educator with over a decade of teaching English in Miyagi, Japan. Holding a Master’s in Teaching for Primary Education from the University of New England in Australia, Kye’s diverse career also includes experience as a homeroom teacher in Sydney. Passionate about building dynamic and engaging classroom environments, he focuses on encouraging active language use and supporting students at every stage of their language learning journey. kmarkste@gmail.com