Over the years, most teachers of children that I’ve met were avid readers when they were young and assumed that their students would be the same. I taught myself to read and was the kind of child who would walk into walls because I was simultaneously trying to read a book. Entering a library was exciting and akin to finding a treasure chest filled with jewels. Therefore, it was sometimes hard for me to put myself in the shoes of children who might not be as enthusiastic about reading books, especially ones written in a foreign language. However, I needed to do so for my school’s extensive reading (ER) program to be successful.

What Is Extensive Reading?

Extensive reading is an approach where students choose and independently read a large number of books, ideally at or slightly below their reading level as a way to receive a large amount of comprehensible input and improve reading skills (Nation & Waring, 2013). In the young learner EFL context, especially in eikaiwa (English language conversation) classes that might only be 50 minutes long, this can be an efficient way for students to get a lot of comprehensible input (Krashen, 1992). ER can be especially valuable for returnee children coming back from English-speaking countries, who used to receive English input naturally in their daily lives and now must rely on books or other sources for that input now that they are back in Japan (Taniguchi, 2021).

Many university ER programs have a target number of words students must meet in order to pass the class, but as eikaiwa schools do not have end-of-semester grades, it is imperative for them to be intrinsically motivated to read in order for the ER program to be successful (Ito, 2024). In any case, there are many studies that suggest that intrinsic motivation is the most powerful factor in getting students to read on their own in their first or second language (e.g., Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Takase, 2007; Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997). As intrinsic motivation is an innate human tendency, it can only be brought out by creating an environment that supports it (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Many teachers misunderstand this important point and ask how they can motivate students to read when they should be asking how they can create an environment where students will be motivated to do so (Gambrell, 1996). Students will be more intrinsically motivated to do ER if the teacher creates an environment where reading is a fun and interesting activity, a wide variety of books at or below their level are provided for checkout, and books are arranged in an easily accessed manner.

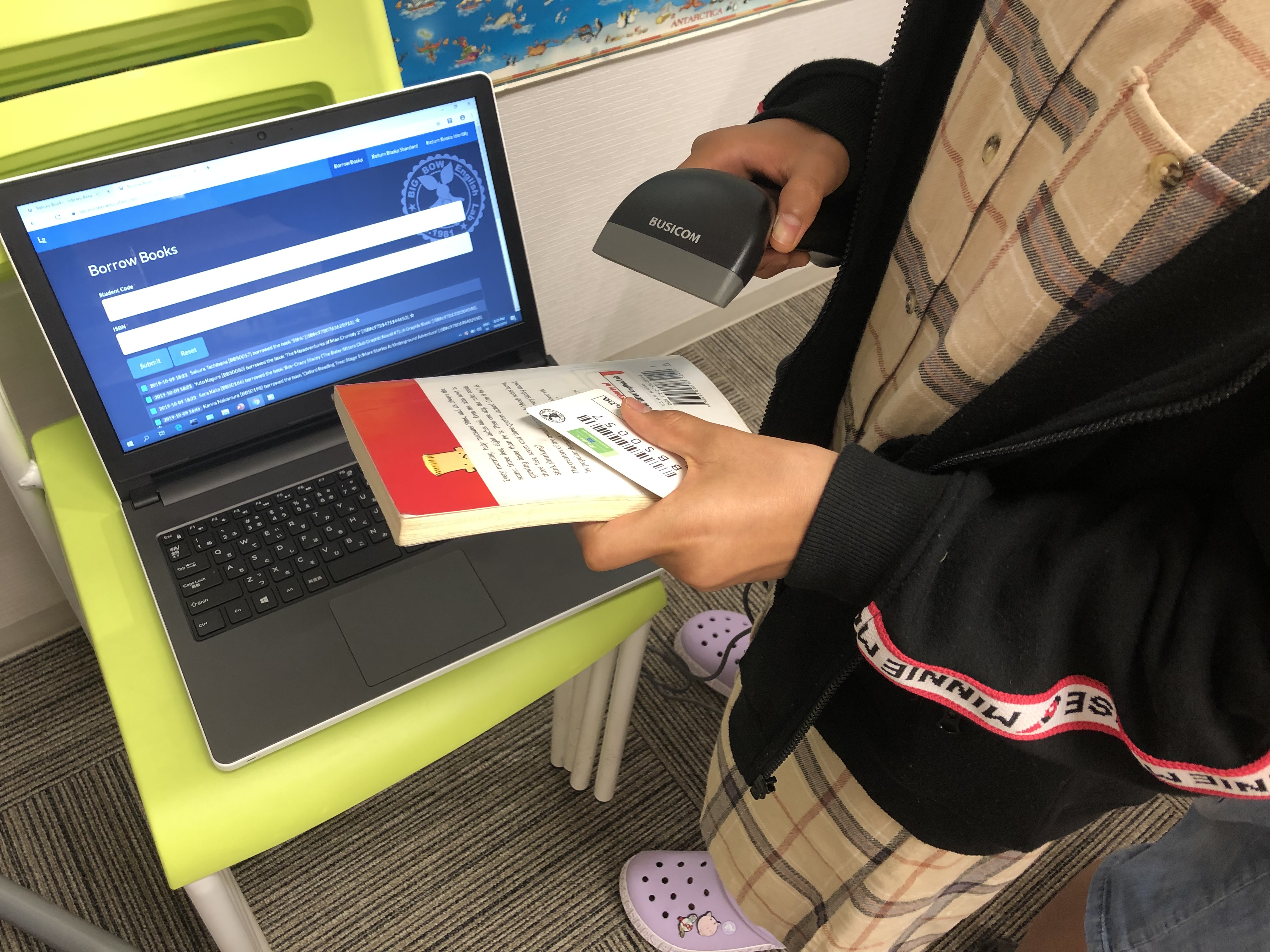

Students at my eikawa school have access to over 1,000 graded readers (some with audio), leveled readers, and authentic materials from our library. As there tends to be an expectation that classes in eikawa schools focus on speaking and listening, sustained silent reading, meaning silently reading self-selected materials in class (Day & Bamford, 1998), would not be feasible in short eikaiwa classes nor receive parental support. Therefore, students check out books from the library to read at home (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Checking out Books to Take Home Using the LIXON Library System

The Action Research Project Begins

The library seemed to be active, but after reading The Book Whisperer by Donalyn Miller (2009), I began to wonder if there was room for improvement. Miller is an inspirational sixth-grade teacher from Texas, USA, who has her students read 40 novels a year. Her book whispering method entails learning about students’ interests using a questionnaire and then recommends books for them to read. I wondered whether such an approach could work with EFL students in an eikawa school. An action research project was started, with the initial plan of half of the students receiving book whispering and the other half as a control group.

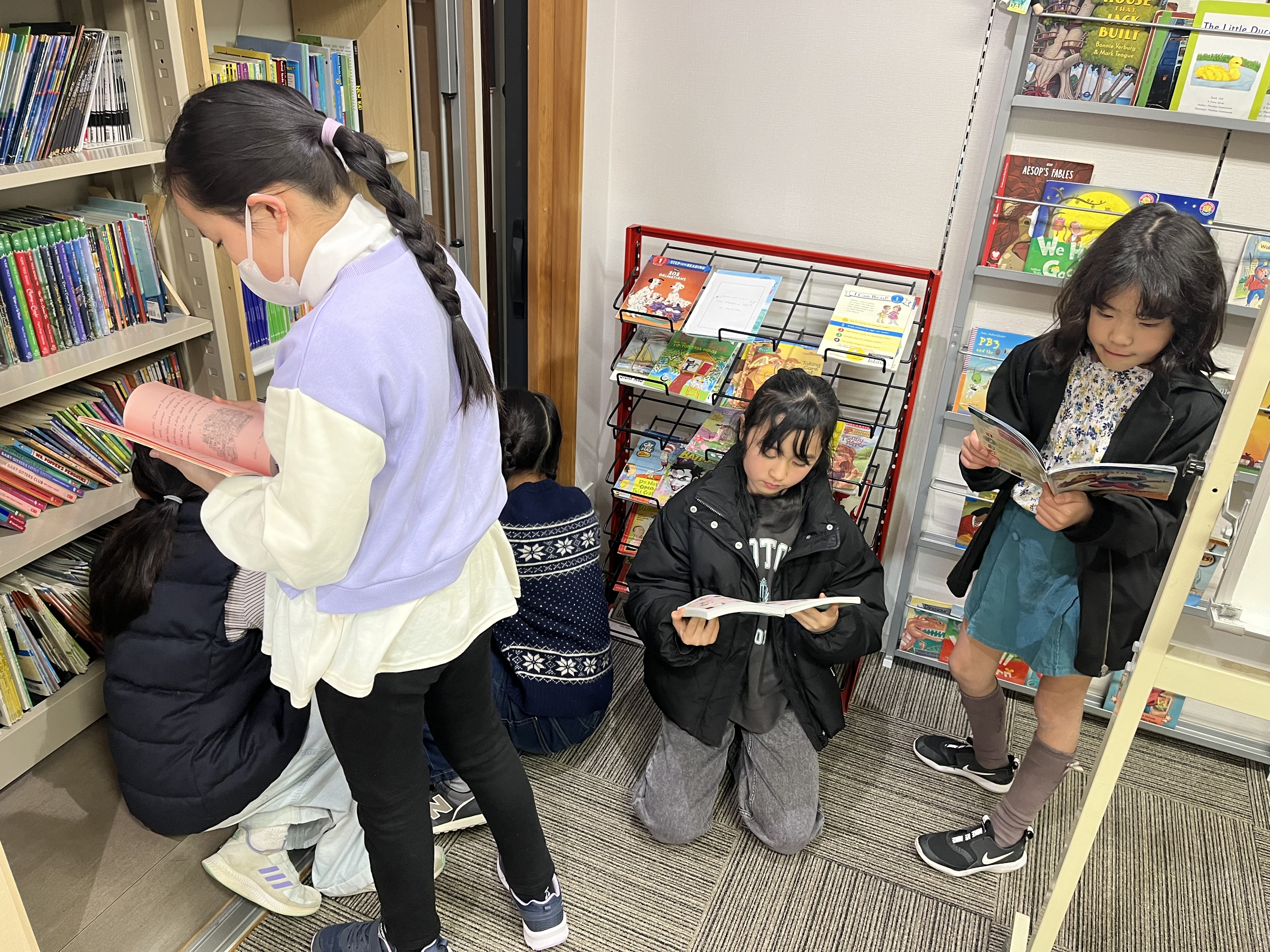

A baseline bilingual smiley questionnaire—a child-friendly Likert-like questionnaire using smiley faces—created using the Early Language Learning in Europe guidelines (Enever, 2011) was given to 91 young learners to begin the action research project. These students ranged in age from six to 16. There were 42 Japanese EFL students, and 49 were either returnees, graduates of international pre-schools, or had at least one parent from an English-speaking country. The questionnaire focused on attitudes on reading, reading activities in the class, the ER program, as well as how much they welcomed help from the teacher in selecting books to check out. Some of the results were very comforting: almost half said they liked reading in English, and 70% reported usually reading the library books they checked out (see Figure 2). However, the questions about receiving help from the teacher were overwhelmingly negative. Over two-thirds of the students reported that they liked choosing library books by themselves, 15% welcomed the teacher’s help, and only 9% wanted more help. One interesting contradiction was that 40% said they had trouble finding books they liked, yet they did not want direct help from the teacher.

Figure 2

Students Choosing Books on Their Own From the School Library

Two separate follow-up questionnaires were sent out about receiving help from the teacher: one questionnaire to the 75 students who gave negative or neutral responses about receiving teacher help and another to the 16 students who responded positively. Students who did not want the teacher’s help had strong opinions about what they liked and wanted to choose reading materials on their own. These students felt obligated to check out what the teacher suggested and then sometimes felt resentful because their autonomy had been infringed upon. Some of the questionnaire comments were brutally honest. Examples of these are presented below:

I don’t like insect books, but when the teacher says, “How about this insect book?” I can’t say no. (translated from Japanese)

Because I can choose my favorite books just myself.

Just stay and I’ll do the read and choose.

Students who had a positive response of receiving help from the teacher often had trouble finding suitable books that matched their interests or reading level or wanted recommendations for something new. After reading their responses, I began to realize these were often students who successfully found a book they liked after my recommendation. Considering that students often come to school for years and I get to know them fairly well, it was shocking that my success rate was so low!

After analyzing the results of the second questionnaire, it became apparent that the initial action research plan investigating book whispering had to be scrapped, and indirect book recommendation methods needed to be researched instead. The teacher reading aloud (TRA) approach was first chosen based on a successful case study of a California teacher who read books aloud to students during class and then noticed that not only were these books more likely to be checked out by students, but it helped the class library become a shared experience (Brassell, 2003). I also implemented the peer-to-peer recommendation (PTPR) technique, which I had experience in my university classes through a book talk activity—students spend a minute verbally recommending a recently read book to classmates in small groups. Other approaches used with children were considered, such as a student-curated pupil recommendation shelf (Biddle, n.d.) or a library pocket, where students insert written book recommendations into a classmate’s designated envelope (Mrs. Carter, 2010).

Second Cycle of Action Research

For the second cycle of action research, seven classes were put in the TRA group and the other seven were put in the PTPR group. Four book series were introduced at two-week intervals for the TRA group (see Figure 3). A book, or a chapter of the book was read to the students in the ten minutes before library book check-out time. Then, the books were laid face up on the table with the teacher only commenting that they were available for check out. As many of these books were checked out, my initial observation was that this was an effective way to introduce new books to the students.

Figure 3

A Series is Introduced to a Class by the Author

The PTPR group got off to a rocky start. Voice recordings of the students during library time revealed they were not spontaneously recommending books verbally to each other. “Book talk” did not go well with younger students because they complained they did not know what to say, even when given prompts by the teacher. There were also other problems with students not paying attention to the student who was speaking. Finally, a feasible solution was found: recommendation postcards. Each student made two postcards about books they recommended. Students glued a cut-out photo of them holding the book and then wrote a short recommendation. For the next month, these postcards were verbally presented to their classmates right before library check-out time and then displayed in a pocket wall chart. Although students seemed to enjoy the postcard making activity, it required a lot of work from the teacher—taking a photo of a student with the book, printing out the photo, providing sentence writing prompts, and checking the students’ written work. Furthermore, it was observed that students were not consulting the postcards in the pocket wall chart when deciding what books to check out.

A final bilingual questionnaire was given to the TRA and PTPR groups one month after the in-class book recommendation activities ended. The students in the TRA group gave very positive responses about the teacher indirectly recommending books by reading them aloud. An overwhelming majority (83%) said they liked it when the teacher read books aloud, 69% said this made them interested in the series, and 50% said it made them want to check out more books from the library. Most of the comments expressed a desire to borrow the book or series read aloud by the teacher. Students who said they liked reading in English increased by 15%, compared to the results of the baseline questionnaire.

The results of the PTPR questionnaire were also positive, but making the postcards was rated as more enjoyable (59%) than verbally recommending the book to their classmates (41%). However, a majority (59%) said they enjoyed listening to classmates recommend a book and were interested in checking out these peer-recommended books (59%). One interesting data point was that EFL students enjoyed making the postcard more and were more interested in checking out peer-recommended books than returnee students. Another interesting result was that less than half of the student comments were about recommending books to classmates, and the remaining comments were about how fun it was to make the postcard or how it was a good writing practice. It seemed the purpose of the activity—recommending books to classmates—somehow got lost. Even though students who said they liked reading in English increased by 10%, compared to the baseline questionnaire results, students who thought doing ER at home helped improve their English decreased by 15%.

Sometimes there is a large gap between what students say and what they actually do, and this was the case with the PTPR group. Book borrowing data recorded using the LIXON Library system was analyzed from two or three months before the action research project began until the end. The borrowing behaviors of the TRA students reflected their positive responses on the questionnaire. Before the action research project began, they borrowed books from the recommended series four times, but after the TRA, these were borrowed 106 times. In contrast, the PTPR group borrowed more of the recommended books before the action research even started. Of the 78 recommended books, only 12 were borrowed by students after the peer recommendation. However, 44 were borrowed before the action research project began (eliminating the student who recommended the book). Another interesting point was that younger students sometimes recommended books they had never borrowed.

Action Research Findings and Conclusions

The purpose of action research is to identify areas in the classroom that need improvement, deciding what can be researched, collecting and analyzing data, bringing about a change, and then evaluating the effects these changes brought to the learning environment (Boon, 2016). In this case, I was able to find out that TRA has a strong positive effect on my students’ intrinsic motivation to do ER, as confirmed by the data on their book borrowing behaviors. It was also the method that was easiest and most efficient for the teacher to implement, requiring little preparation and only ten minutes of class time. PTPR, on the other hand, required a lot of class time and scaffolding by the teacher to make the postcards. It was also less effective because students did not borrow the books their classmates recommended and it seemed many students viewed this as a craft making/writing activity, rather than an ER one. Based on these results, the decision was made to do TRA in class at various times during the school year, especially when new books are introduced to the library.

Another finding of this action research project was how important autonomy was to the students, considering how they preferred indirect methods of recommendation by the teacher. Children feel very strongly about having the freedom to choose what they want to read. In the past, parents have wanted me to choose library books for their children or make them borrow books they deem appropriate. After conducting this research project, I was able to communicate to them how counterproductive this was and how respecting their child’s autonomy would lead to more reading motivation in the long run.

A secondary finding was some methods that worked well in English-speaking countries did not in the eikaiwa context. Book whispering and peer-to-peer recommendation are highly regarded in research conducted in English-speaking countries and with the dearth of research on children and reading motivation in EFL, it can be tempting to assume they can be as successfully implemented in an eikaiwa class in Japan. I welcome more research on children and intrinsic motivation to do ER in Japan, to see if these findings hold true for other language programs in eikaiwa schools.

References

Baker, L., & Wigfield, A. (1999). Dimensions of children’s motivation for reading and their relations to reading activity and reading achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 34(4), 452–477. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.34.4.4

Biddle, J. (n.d.). Pupil recommendations shelf. The Open University: Reading for Pleasure. https://ourfp.org/eop/pupil-recommendations-shelf/

Boon, A., (2016). The action research cycle: Exploring pedagogic puzzles. Sage Research Methods Cases Part 2. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473991019

Brassell, D. (2003). Sixteen books went home tonight: Fifteen were introduced by the teacher. The California Reader, 36(3), 33–39.

Day, R. R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Enever, J. (Ed.). (2011). ELLiE: Early language learning in Europe. The British Council.

Gambrell, L. B. (1996). Creating classroom cultures that foster reading motivation. The Reading Teacher, 50(1), 14–25.

Ito, L. (2024). Children and extensive reading motivation: An action research project on extensive reading motivation in a private language school. Language Teaching for Young Learners, 6(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.00046.ito

Krashen, S. (1992). The input hypothesis: An update. In J. E. Alatis (Ed.), Linguistics and language pedagogy: The state of the art (pp. 409–431). Georgetown University Press.

Miller, D. (2009). The book whisperer: Awakening the inner reader in every child. John Wiley & Sons.

Mrs. Carter. (2010, April 9). Happy spring break to you all! Mrs. Carter’s Calling. http://mrscarterscalling.blogspot.jp/2010/04

Nation, P., & Waring, R. (2013). Extensive reading and graded readers. Compass Media. https://www.readingoceans.jp/ComData/files/Paul%20Nation%20%20Rob%20Waring’s%20ER%20Booklet_eng.pdf

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Takase, A. (2007). Japanese high school students’ motivation for extensive L2 reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 19(1), 1–18. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ759837

Taniguchi, J. (2021). Biliteracy in young Japanese siblings. Hituzi Shobo.

Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading to the amount and breadth of their reading. Journal of Education Psychology, 89(3), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.420

Lesley Ito is a well-known teacher, teacher-trainer, school owner, and award-winning materials writer based in Nagoya. She has taught in Japan for over 30 years and is the owner of LIXON Education and BIG BOW English Lab in Nagoya. She won Best of JALT in 2011 and 2020, and has presented throughout Japan, KOTESOL, and at the ER World Congress in Dubai, UAE. Winner of the 2015 LLL Award in the Young Learner Category for Backstage Pass, her ELT writing credits include teacher’s guides, workbooks, and graded readers.