The emphasis of pronunciation teaching has generally been on the accurate articulation of an inventory of vowels and consonants, that is, the segmental aspects of language (Dalton & Seidlhofer, 1994). Unfortunately, this approach may underestimate the true nature of pronunciation and, as Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwin maintain, "a learner's command of segmental features is less critical to communicative competence than a command of suprasegmental features" (1996, p. 131). While recognizing that segmental and suprasegmental features operate in unison with each other, this paper focuses on suprasegmentals of pronunciation and encompasses (a) a comparison of these features in English and Japanese, and (b) a description of how the similarities and differences thus identified might be used to raise Japanese learners' awareness of this aspect of English pronunciation. The accents used as models for discussion in this paper are "BBC" pronunciation (Roach, 2000) for English and standard Japanese (Martin 1992), Tokyo dialect.

There appears to be a general consensus among scholars (Clark & Yallop, 1995; Cruttenden, 2001) that suprasegmentals are those features that operate above and beyond the level of individual sounds, consonants, and vowels. Suprasegmental features are also referred to as prosodic features (Clark & Yallop, 1995) and prosody (Cruttenden, 2001).

The major suprasegmental features are stress, rhythm, and intonation (Jenkins, 1998; Roach, 2000) and these features are shaped by the dynamic patterns of pitch, duration, and loudness (Clark & Yallop, 1995). Furthermore, these patterns are superimposed on and influenced by less dynamic voice quality settings (Pennington & Richards, 1986).

Voice quality settings refer to the long-term articulatory postures of a speaker which determine the overall pattern of suprasegmental features that characterize the voice of the speaker and the accent of the speaker's particular language (Esling & Wong, 1983). Voice quality settings will differ in pitch range (Dalton & Seidlhofer, 1994) and "in tension, in tongue shape, in pressure of the articulators, in lip and cheek and jaw posture and movement" (O'Connor, 1973, p. 289).

English settings

A broad model of English voice quality settings might include features such as loosely closed jaws, lips and jaws which move little, relaxed cheeks (Thornbury, 1993), a nasal voice, and a palatalised tongue body position (Esling & Wong, 1983). Kenworthy (1987) states there is little overall difference in voice quality settings between males and females and notes that both genders utilize high overall pitch when expressing politeness.

Japanese settings

Japanese speakers also generally utilize minimal lip and jaw movement (Thompson, 1987). Japanese male voice quality settings include a lowered larynx and uvularization with lip spreading (Esling & Wong, 1983) resulting in a deep rumble or a hoarse or husky sound (Pennington & Richards, 1986). In contrast, Japanese females are apt to be breathy (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996) and distinctly more nasalized and high-pitched than Japanese males (Kristof, quoted in Chan 1997). Recent research indicates that the pitch of female voices has begun to lower. It has been suggested that this change is connected with the increased economic and political influence of Japanese women (O'Neil, 2000).

Raising awareness of voice quality settings

Thornbury (1993) presents tasks designed to promote awareness that could be employed with Japanese learners, such as using recordings of a task performed by a Japanese speaker of English and a native speaker to note similar and different characteristics, followed by a discussion of these characteristics. Jones and Evans (1995) suggest tasks that focus learners on English voice quality settings in various contexts in order to increase confidence and improve learner self-image when speaking English.

Voice quality settings often differentiate individuals according to social status in both Japanese and English. Although Japanese women are generally able to access the higher pitch range expressing deference or politeness in English, Japanese males often find this setting to be feminine (Loveday, 1981). Another problem for Japanese males is that their voice quality settings often make them sound monotonic in English. Encouraging Japanese males to use suitable phrases, gestures and facial expressions may compensate for both these problems related to low pitch level (Kenworthy, 1987).

English stress

English is a stress accent language, where stress refers to the way in which pitch, duration, and loudness combine to give certain syllables greater prominence than others (Roach, 2000). Of the three dimensions, pitch and duration are the most salient determinants of stress, with loudness playing a less significant role (Clark & Yallop, 1995).

Stress functions at both the word level

as word stress and at the sentence level as sentence

stress. There are three levels of word stress: primary stress,

secondary stress, and unstressed. Most unstressed syllables contain

/I/ or the neutral schwa vowel![]() (Swan,

1995). Furthermore, schwa is the most frequent sound in English

and occurs in almost every word that is longer than two syllables

(Kenworthy, 1987). Another feature of word stress in English is

that it nearly always falls on a specific syllable of any particular

word (Cruttenden, 2001). Kenworthy (1987) provides a useful summary

of English word stress rules.

(Swan,

1995). Furthermore, schwa is the most frequent sound in English

and occurs in almost every word that is longer than two syllables

(Kenworthy, 1987). Another feature of word stress in English is

that it nearly always falls on a specific syllable of any particular

word (Cruttenden, 2001). Kenworthy (1987) provides a useful summary

of English word stress rules.

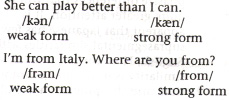

Not all words receive the same amount of stress at the sentence level in English. As Celce-Murcia et al. (1996) propose, content words -- words that carry information, such as verbs, nouns, and adjectives -- are usually stressed, whereas function words -- words that indicate grammatical relationships, including articles, auxiliary verbs, and prepositions -- are typically unstressed.

Japanese is a pitch accent language in which all syllables maintain the same perceived duration whether or not they are accented (Takeuchi, 1999). Furthermore, there is no discrimination between word or sentence level stress in Japanese.

According to Kindaichi (1978), Takeuchi (1999), and Tsujimura (2000), the main characteristics of Japanese pitch accent are as follows:

hashi ga chopsticks High Low Low (first syllable accented) hashi ga bridge Low High Low (second syllable accented) hashi ga edge Low High High (un-accented)

The very limited parallels between Japanese accent and English stress mean that English stress patterns have to be deliberately learnt and practiced (Thompson, 1987). However, Japanese learners respond well to clear explanations, such as with the presentation of word stress rules, which may be followed by categorization activities aimed at highlighting lexical tendencies (e.g. classifying words as a verb or a noun -- for example, record -- according to stress pattern), and stress pattern games (see Hancock, 1996).

Raising learners' awareness of the high occurrence of schwa is a priority and this may be achieved through consistently eliciting word stress and schwa, appropriate modeling, choral and individual drilling. According to Thompson (1987), another area that Japanese learners have problems with is English loan words, due to the accent usually being placed on the third-to-last syllable of such words. This accent pattern often leads to mispronunciation that may be overcome with time and effort by employing those measures mentioned with regard to word stress and schwa.

English Rhythm

English is generally considered to have a stress-timed rhythm that is essentially created by the combination of word and sentence stress (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996). However, there is no firm evidence for the existence of stress-timed regular rhythm in English (Marks, 1999; McCarthy, 1991; Roach, 2000) and it may be "no more than a convenient fiction for the classroom" (Jenkins, 1998, p.123).

Connected speech

In connected speech, content words maintain some level of prominence throughout (Cruttenden, 2001). However, as Roach (2000) mentions, function words have two forms -- a strong form (in particular situations or when uttered in isolation) and a weak form (which is the more usual, unstressed form):

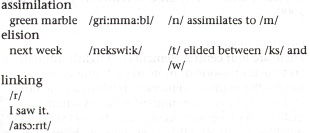

In order to facilitate the relative regularity of English rhythm in connected speech, other adjustments need to be made (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996).

(For further details see Dalton & Seidlhofer, 1994; Kelly,

2000; Kenworthy, 1987)

Japanese rhythm

Japanese is considered to be a syllable-timed language because

all syllables are pronounced with equal duration. There is no

strong pattern of stress, and rhythm "is a function of the

number of syllables in a given phrase, not the number of stressed

elements" (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996, p.153).

In Japanese, modifications in connected speech are apparent in

both function and content words (Tsujimura, 2000):

| Kuru no nara | Kuru n nara | if it is that you come |

| Shiranai | Shi n nai | don't know |

| Atarimae | Atarimee | of course |

However, these alterations have little to do with maintaining rhythm as they do in English, as the syllable count and syllable duration in Japanese always remain consistent regardless of the adjustments described. Rather, they occur as a result of an increase in articulation rate or the use of casual speech (Tsujimura, 2000).

Raising awareness of stress-timed rhythm

In general, most Japanese learners have an awareness of English stress and are relatively good at recognizing and repeating the rhythmical patterns of English at a slower tempo. However, incorporating features of connected speech when repeating utterances at a more natural rate causes considerable difficulties. Therefore, remedial awareness-raising activities need to be provided, including the use of phonemic transcripts to highlight features of connected speech, clear modeling of voice quality settings, emphasizing rhythm by clapping on stressed syllables in contrast to unstressed syllables, and teaching ideas built around strongly rhythmical material such as nursery rhymes, limericks, songs, and jazz chants (see Laroy, 1995; Means, 1998). In addition, Kelly (2000, pp.116-121) provides sample lessons focusing on weak forms, assimilation, elision, and linking.

Intonation describes the way different kinds of meaning are conveyed in discourse through the use of pitch patterns (Dalton & Seidlhofer, 1994; Roach, 2000).

English intonation

There are four central elements of English intonation: (a) tone units -- one or more in each utterance; (b) tones -- the main movement of pitch in a tone unit; (c) tonic syllables -- prominent syllables where the main pitch movement occurs; and (d) onset syllables -- syllables which establish a constant pitch (or key)1 up to the tonic syllable (Brazil, 1997). These elements are indicated using conventional notation in Figure 1.

There is generally one tonic syllable in one tone unit (Roach, 2000) and this usually signals new information (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996) and typically occurs in the last lexical item of a tone unit (Kelly, 2000). Celce-Murcia et al. (1996) suggest the use of emphasis or contrast in discourse, and situational context plays a significant role in determining the tonic syllable in a given tone unit.

Brazil (1997) identifies five possible tones in discourse -- a level tone, two proclaiming tones, and two referring tones. Proclaiming tones are used by the speaker to (a) express information believed to be new, (b) add something to the discussion, or (c) ask for new information. In contrast, referring tones are used when the speaker refers to shared information (Kelly, 2000). The two alternatives speakers may choose for each type are shown in Figure 2 with the tones r and p being more frequent than r+ andp+.

Japanese intonation

Japanese intonation has much shorter and less exaggerated peaks than English (Celce-Murcia et al., 1996); its pitch level transitions appear to be more abrupt (Kenworthy, 1987). It does not highlight new or shared information, and many of the attitudinal patterns expressed through intonation in English are done so in Japanese using adverbials and particles (Thompson, 1987). Basically there are only two tones -- rising for questions or falling for statements (Tsujimura, 2000), and these tones are usually restricted to the last syllable of an utterance (Martin, 1992).

Raising awareness of intonation

Whereas the link between certain grammatical structures and intonation patterns is helpful to a degree, intonation is probably "best dealt with in clear contexts...with ample opportunity for both receptive and productive work" (Kelly, 2000, p.106). For Japanese learners, transcripts and audio or visual recordings of authentic spoken discourse could be used to provide opportunities for comparison, prediction, and perception -- in context -- of tone patterns and tonic syllables (particularly in the use of emphasis and contrast, as these are often inhibited due to Japanese social custom norms). Bradford (2000), Levis (2001) and Roberts (1983) suggest employing techniques such as memorizing and acting out dialogues, performing drills applied in different contexts with a range of emotions and attitudes, and opportunities for freer practice through role-plays or simulations. Furthermore, a useful method to utilize is hyper-pronunciation, where learners are encouraged to deliberately exaggerate intonation patterns (Todaka, quoted in Celce-Murcia et al., 1996).

Suprasegmental pronunciation is of significant communicative importance in discourse. For teachers of English in Japan, one way to raise learner awareness of suprasegmental features of pronunciation may be through the recognition and comparison of these aspects in English and Japanese in order to highlight similarities or to emphasize differences that will require greater attention. It is apparent that Japanese has few suprasegmental similarities with English. Nonetheless, one key similarity is in the area of intonation, and this provides a useful point of reference. With regard to the numerous differences, it is worthwhile prioritising them according to teachability, learnability and their influence on intelligibility (Jenkins, 1998). In short, this paper has attempted to illustrate that an analysis of the similarities and differences between English and Japanese pronunciation is a useful, and perhaps necessary, starting point for gaining a better understanding of those suprasegmentals of English which require particular attention.

Note

1. A high key may be used for contrast, a mid key for addition, and a low key for natural follow-on (Coulthard, 1985).

Bradford, B. (2000). Intonation in context -- Student's book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brazil, D. (1997). The communicative value of intonation in English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. (1996). Teaching pronunciation: A reference for teachers of English to speakers of other languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chan, M. (1997). Gender differences in the Chinese language: A preliminary report. In H. Lin (Ed.), Proceedings of the Ninth North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL) (Vol. 2, pp. 35-52). Los Angeles: GSIL Publications, University of Southern California. [Electronic version]. Available: <http://deall.ohio-state.edu/chan.9/articles/naccl9.htm> (2002, February).

Clark, J., & Yallop, C. (1995). An introduction to phonetics and phonology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Coulthard, M. (1985). An introduction to discourse analysis. Essex: Longman.

Cruttenden, A. (2001). Gimson's pronunciation

of English. London: Arnold.

Dalton, C., & Seidlhofer, B. (1994). Pronunciation. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Esling, J., & Wong, R. (1983). Voice quality settings and the teaching of pronunciation. TESOL Quarterly, 17(1), 89-95.

Hancock, M. (1996). Pronunciation games. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jenkins, J. (1998). Which pronunciation norms and models for English as an International Language? English Language Teaching Journal, 52(2), 119-126.

Jones, R., & Evans, S. (1995). Teaching pronunciation through voice quality. English Language Teaching Journal, 49(3), 244-251.

Kelly, G. (2000). How to teach pronunciation. Essex: Longman.

Kenworthy, J. (1987). Teaching English pronunciation. Essex: Longman.

Kindaichi, H. (1978). The Japanese language. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing Company.

Laroy, C. (1995). Pronunciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Levis, J. (2001). Teaching focus for conversational use. English Language Teaching Journal, 55(1), 44-51.

Loveday, L. (1981). Pitch, politeness, and sexual role. Language and Speech, 24(1), 71-89.

Marks, J. (1999). Is stress-timing real? English Language Teaching Journal, 53(3), 191-199.

Martin, S. (1992.) Essential Japanese. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing Company.

McCarthy, M. (1991). Discourse analysis for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Means, C. (1998). Using chants to help improve rhythm, intonation, and stress. The Language Teacher, 22(4), 38-40.

O'Connor, J. (1973). Phonetics. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

O'Neil, D. (2000). Hidden aspects of communication. [Electronic version]. Available: <http://anthro.palomar.edu/language/language_6.htm> (2002, February).

Pennington, M., & Richards, J. (1986). Pronunciation revisited. TESOL Quarterly, 20(2), 207-225.

Roach, P. (2000). English phonetics and phonology (3rd ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, J. (1983). Teaching with functional materials: The problems of stress and intonation. English Language Teaching Journal, 37(3), 213-220.

Swan, M. (1995). Practical English usage.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Takeuchi, L. (1999). The structure and history of Japanese.

New York: Pearson Education Limited.

Thompson, I. (1987). Japanese speakers. In M. Swan & B. Smith (Eds.), Learner English (pp.212-223). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thornbury, S. (1993). Having a good jaw: Voice setting phonology. English Language Teaching Journal, 47(2), 126-131.

Tsujimura, N. (2000). An introduction to Japanese linguistics. London: Blackwell Publishers.

Further Reading

http://user.gru.net/richardx/pronounce2.html

http://www.public.iastate.edu/%7Ejlevis/SPRIS/

http://www.ntu.edu.au/education/langs/jpn/intro/intro4.htm

http://polyglot.cal.msu.edu/llt/vol2num1/article4/

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editors and two anonymous reviewers for comments on this paper.

Jeremy Cross has been teaching English at the British Council in Nagoya since 1998. He holds a DTEFLA and is currently studying towards an MA in Linguistics (TESOL) by distance learning through the University of Surrey.